The global financial crisis began ten years ago: HSBC issued a profit warning linked to bad debts, the first of sign of trouble in the U.S. housing market. Finance expert Adriano B. Lucatelli looks in an essay for finews.first at how the damage spread.

finews.first is a forum for renowned authors specialized on economic and financial topics. The texts are published in both German and English. The publishers of finews.com are responsible for the selection.

On February 7 of 2007, British banking giant HSBC surprised markets with a profit warning connected to write-downs on US subprime mortgages. No-one had any inkling that this was the opening act of what would be the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression began in 1929. The 2007 crisis even eclipsed Black Monday, the stock market crash of 1987, and the collapse of the dotcom bubble of 2000.

After HSBC’s loss report, the disaster gathered pace. On August 9 of the same year, the French bank BNP Paribas announced that it was ceasing activity in three investment funds that specialized in U.S. mortgage debt, and were de facto insolvent. The following month saw a bank run on the British mortgage lender Northern Rock.

Customers queued outside branches for hours, hoping to withdraw their savings. Northern Rock could no longer survive alone and was taken into public ownership by the British state on February 22 of the following year.

«The crisis reached its peak on September 15 with a cluster of events»

In March of 2008, the once-proud investment bank Bear Stearns allowed itself to be taken over by J.P. Morgan Chase for $236 million, to avoid bankruptcy.

The crisis reached its peak on September 15 with a fury of events. Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, and Merrill Lynch was taken over by Bank of America for $50 billion. The Dow Jones Index suffered its worst single-day loss since the terror attacks of September 11, tumbling 777.68 points to close just over 10,000 points.

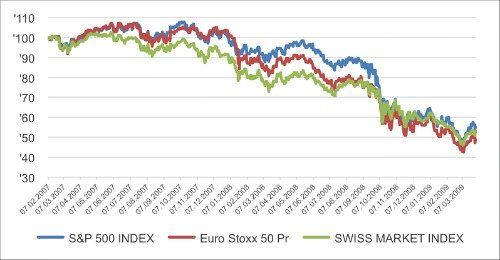

Stock Market Movement During the Crisis

(Source: Bloomberg)

How do things look ten years later? Judging by the situation in the U.S., everything seems to be in order. The normalization of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve late in 2015 marked the official end of the financial crisis. The S&P 500 and the Dow Jones have long overtaken pre-crisis values. Since Donald Trump’s election, they’ve even reached new all-time highs.

All’s well that ends well? Not quite. In the eurozone, the outlook is still predominantly gloomy. To save the crumbling banks, governments have had to inject billions. This created a sovereign debt crisis that threatens the survival of Europe's single currency.

«After ten years of stagnation, rates of prosperity, employment and savings are on the floor»

In Europe, the crisis has already claimed its first victim: Greece. The country lies in ruins, and it is not clear how Greece will ever pay back its debts. Without debt relief, Greece would hardly be able to stand on its own feet again, and Grexit would be inevitable. Trouble is also brewing in Italy.

After ten years of stagnation and three of recession, rates of prosperity, employment and savings are on the floor. As a result, populist powers have gained political weight, and the «five-star movement» has even promised a referendum on eurozone membership.

«If they do not, there will be extremely stormy years ahead»

It is still too soon to say that Europe has overcome the financial crisis. Instead, Europe's unity project remains under threat. The eurozone countries must therefore face up to the removal of the structural weaknesses that were uncovered by the crisis, and introduce sustainable reforms. If they do not manage to do that, there will be extremely stormy years ahead.

If no effective action is taken, the collapse of the eurozone, if not the entire European Union, could well be the delayed result of the 2007 global financial crisis.

Adriano B. Lucatelli is co-founder and managing director of Descartes Finance, a senior lecturer at the University of Zurich and co-founder of Vormaerz, a think tank promoting the dialogue between companies and the financial market. He studied international affairs and economics at the University of Nevada, Reno and at the prestigious London School of Economics. In 1995 he obtained a PhD from the University of Zurich with a dissertation on global financial market regulation. He started his professional career at Credit Suisse in 1994. From 2002 to 2009, Lucatelli was managing director at UBS Switzerland and member of the management committee in Lugano and Zurich.

Previous contributions: Rudi Bogni, Adriano B. Lucatelli, Peter Kurer, Oliver Berger, Rolf Banz, Dieter Ruloff, Samuel Gerber, Werner Vogt, Walter Wittmann, Alfred Mettler, Peter Hody, Robert Holzach, Thorsten Polleit, Craig Murray, David Zollinger, Arthur Bolliger, Beat Kappeler, Chris Rowe, Stefan Gerlach, Marc Lussy, Nuno Fernandes, Beat Wittmann, Richard Egger, Maurice Pedergnana, Didier Saint-George, Marco Bargel, Steve Hanke, Andreas Britt, Urs Schoettli, Ursula Finsterwald, Stefan Kreuzkamp, Katharina Bart, Oliver Bussmann, Michael Benz, Peter Hody, Albert Steck, Andreas Britt, Martin Dahinden, Thomas Fedier, Alfred Mettler, Frédéric Papp, Brigitte Strebel, Peter Hody, Mirjam Staub-Bisang and Guido Schilling und Claude Baumann.