An activist hedge fund plans to carve up Credit Suisse into three parts has been dismissed as short-term greed. In fact, global universal banks are a dying breed. finews.com explains why.

It may be a little ironic that it needed Rudolf Bohli (pictured below) to question the business model of Credit Suisse (CS). The activist investor is a lightweight with his RBR Capital Advisors hedge fund.

His move may be sheer opportunism and driven by his desire to make a quick buck, and the targets he mentioned for the split-up bank a mirage.

Still, taking a step back from Bohli's plans and ignoring the brouhaha around his personality: the business model of a global universal bank in the vein of Credit Suisse is up for questioning. The consequence: a stronger focus on some units, or even a splitting up of the bank makes sense and is a question of time.

Rivals Reshape

There are numerous reasons for this and signs are that big banks are shrinking and moving towards dividing up into units. In Germany, Commerzbank is in focus but only because of its strong corporate clients business. Deutsche Bank aims to split off its asset management and sell it to investors.

In the U.S., splitting up big banks such as J.P. Morgan, Bank of America and Citigroup has been the focus of a public debate for quite some time. U.S. President Donald Trump had flirted with the reintroduction of the separation of commercial and investment banking under the Glass-Steagall Act from 1933 (pictured below).

Regulators maybe will take care of this in any case – and not only in the U.S. Capital requirements for UBS and Credit Suisse in Switzerland have rendered growth almost impossible to achieve.

Bureaucratic Monsters

Regulatory costs have become a major hinder for global universal banks, restricting their room to maneuver both on an operative as well as strategic level. Big banks are bureaucratic monsters and prone to inefficiencies compared with smaller, focused firms. Their margin is under pressure, which fosters unease among investors.

The wave of fintech companies offering faster and cheaper services have also turned into a major headache for the banking industry. Be it transaction services, loans, wealth and asset management: fintech products rival the business of established banks and put in question the integrated banks such as CS.

Considering these factors, highlighting investing banking was all too logic. And that's what Bohli has done.

What About the Client?

The argument is that the investment bank at Credit Suisse is responsible for the huge regulatory costs, that it requires a lot of capital and that the global markets trading division wouldn't be fit to survive without cheap capital from wealth management and the Swiss bank. Nothing new there – activist investors have used them before, most recently when Knight Vinke hedge fund leveled them at UBS, unsuccessfully.

Evidently, it was the acquisition of First Boston that made Credit Suisse the leading foreign investment bank in the U.S., helping it achieve a global standing. The main beneficiaries of this were bankers who increased their salaries and bonuses.

The client's interests were long secondary to their argument: what is the sense in uniting such disparate business activities like investment and retail banking under one roof? What value is it to clients to entrust his or her funds to such a complex and risky organization?

Case Wears Thin

Credit Suisse and UBS never tire of highlighting the synergies between the two arms, especially ultra-rich clients and capital markets services. This may be true, but can also be maintained with a markedly thinner and more focused organization. Credit Suisse's global markets division is still bulky after a restructuring, and still involved in business areas which burden the bank with costly regulatory capital.

Credit Suisse's response, that it expects to «deliver measurable value for shareholders,» wears thin considering the complex structural challenges that await as well as its organizational deficiencies.

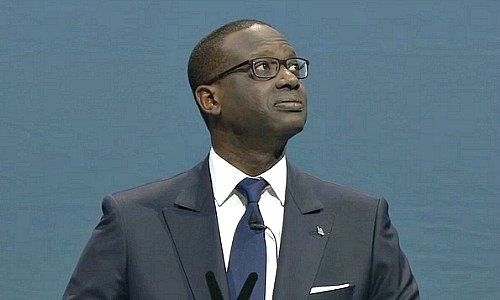

Thiam's «What Now» Moment

The only valid argument against a – short-term price-driven – split of a major bank such as Credit Suisse is the complexity of the undertaking. To begin with, it would mean immense costs and also tie up valuable management resources.

As finews.com has previously reported, Credit Suisse boss Tidjane Thiam (pictured above) is facing his «what now» moment before a three-year restructuring has been concluded. Investors are eager for more than simply a continuation of strategy, and Credit Suisse will struggle to deliver the value it promised.

Radical steps like the carve-up that Bohli is urging could cause more damage or destroy more value than create given the enormous complexity of the task. Spin-offs of individual divisions, like Credit Suisse's investment bank, could be a start though. The size and complexity that Credit Suisse still embodies aren't a sustainable model for the future.