UBS is peddling a one percent advance in quarterly profit as a sensation – likely to relieve pressure on embattled CEO Sergio Ermotti. Instead, the Swiss banker wants to counter a revolution in finance with a slow evolution.

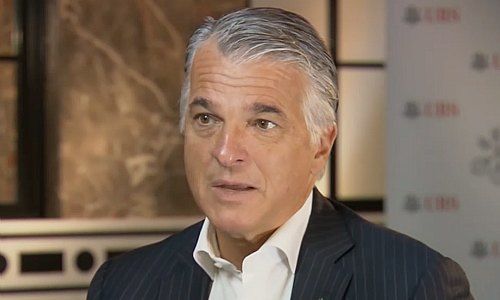

Maybe he didn't have one to hand, or perhaps it was his way of conveying zen and placidity: Sergio Ermotti eschewed his tie during the obligatory «Bloomberg» broadcast interview to mark second-quarter results.

Going tieless is no longer a revolution in the C-suite of banking (as Jamie Dimon showed, three years ago). And that seems to suit Ermotti, who has made two key decisions for the Swiss bank in his eight years at the helm.

Overhaul, then Mega-Merger

The first, of course, was UBS' abandonment of large parts of its investment bank in 2012, 11 months into Ermotti's tenure. The second came just last year, when Ermotti suddenly merged a U.S. brokerage with a wider, international private bank to a global «super division».

In the six years between those two steps, UBS has mastered the art of evolution via moderate and unhurried steps. Ermotti, a 59-year-old former investment banker, has put the kibosh on any other debate over strategic steps by arguing the risks outweigh the potential benefit. In short, UBS would rather do nothing than something daring.

Doing Nothing Not an Option

He is quickly learning that shareholders view doing nothing, against the backdrop of global finance under attack by technology, negative interest rates, and ever-encroaching regulation, as not much of an option.

To be sure, the Ticino native flagged «tactical» and «increasing» spending cuts in a call with analysts and media following the latest results. He talked up alpha and beta factors for weighing on costs and eating into revenue, as well as to measures to mitigate these effects.

Master at Managing Expectations

He also quickly vanquished any excitement that arose over a strategic review to be completed this quarter: Ermotti wouldn't be Ermotti if he didn't. «I'm not thinking of a revolution, but a continuous evolution,» he said.

UBS will define a series of measures, some of which will be made public – some not. Ermotti, who was with UBS just seven months before a $2 billion rogue trading scandal catapulted him into the top spot, has mastered the art of expectations management in the way financial markets understand.

Steering UBS Towards Deals

Ermotti did signal that he is more willing to nudge UBS, a reluctant dealmaker at best, towards acquisitions of tie-ups like a recently inked one with Japan's Sumitomo. He flagged a series of talks on partnerships, including in investment banking and in infrastructure.

«We've proven our competitiveness, we're coming from a position of strength, and we see no reason to deviate from our strategy,» Ermotti said following the results. It is commendable when major companies and CEOs don't buckle at the first hint of criticism over a poor share price.

Shot Across the Bow

But neither is it a sign of UBS's strength that the bank continues to blame outside factors – passive clients, low and negative interest rates, a dent in financial market trading volumes – for its problems. The «new» common sense is that these are factors which finance industry captains are paid to deal navigate around.

Or as Ermotti would put it: if the beta factors aren't producing growth (which they haven't for some time now), then leaders have to look at alpha factors – strategy, spending, and so on – for help. There is no indication that Ermotti is waking up to the increasing urgency for UBS to react. Instead, second-quarter results reek of scraping the bottom of the barrel to remove some of the pressure on Ermotti.

Embarrassing reporting from @sjhmorris at the FT. First he reports the wrong consensus number for the IB. Upon realizing the significant consensus beat, seeing positive reactions from analysts & strong comparison to US peers, his basic story.... doesn't change. Agenda journalism?

— UBS (@UBS) July 23, 2019

Despite mentioning «record» results nine times on 13 pages, UBS' facade is beginning to crumble. The wealth management giant blinked when it attacked a «Financial Times» journalist over what it termed «agenda journalism» after the British newspaper reported on UBS' revenue drops in wealth management and investment banking. These things rarely end well.