Credit Suisse’s asset management deliberations come against the backdrop of renewed pressure on banks to make more of the activities. A French blueprint provides potential clues.

The Zurich-based bank is taking the next 12 months to review the «Varvel barbell,» CEO Thomas Gottstein said four weeks ago. He was referring to the two-pronged asset management strategy is has pursued under Eric Varvel since 2015.

The unit's high-margin products like private equity and an exchange-traded fund business, with little active fund management in between, has flourished since Gottstein’s predecessor, Tidjane Thiam, folded it into a wider private banking unit in 2015: pre-tax profit, as well as assets under management, have risen every year since then.

Given its heft, the bank is deliberating carving asset management back out to stand on its own, according to two insiders. A spokeswoman didn't comment. The organizational tweak could signal that Credit Suisse is ready to head to the market with its asset management arm.

Popular With Pension Funds

It would also give a public face to the unit, which has effectively been leaderless since it was folded into an area managed at the time by Iqbal Khan. The unit's bright spots include a New York-based credit shop and a quantitative equity business formerly known as HOLT that is popular with Swiss pension funds.

The Swiss bank isn’t alone: just about every European lender is rethinking what to do with their asset management arms, according to experts. They are finding it tough to compete with giants like Blackrock.

«There’s lots of interest around European banks combining their asset managers to create more successful shared businesses,» Ben Phillips, a principal with the Casey Quirk strategy practice at Deloitte, told finews.com. «Nearly everyone is open to the idea – if they can be the 51 percent owner,» he added. The reluctance to accept the marginally smaller share has been a stumbling block until now.

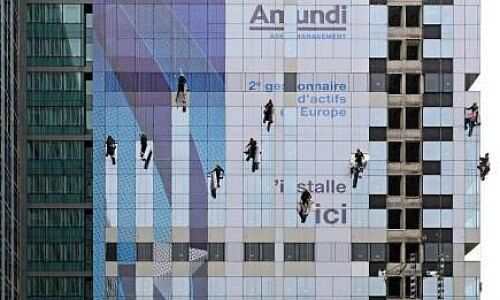

French Blueprint

The blueprint for European asset manager’s is the 2010 merger of Société Générale’s and Crédit Agricole’s respective money-management units into Amundi. The idea is to split revenue and share costs, and hand off the onus of actually operating it.

Under CEO Yves Perrier, Amundi has made acquisitions a pillar of its strategy to compete with giants like Vanguard. It snapped up Italian asset manager Pioneer from Unicredit in 2016. In June, Amundi wrapped a 430 million euro ($500 million) deal for Sabadell’s asset management activities.

Showcasing An Asset

UBS, which recently sniffed around Deutsche Bank’s DWS asset management arm, is simply further along in the process; the Swiss giant had tried unsuccessfully for years under a previous head, John Fraser, to sell it. UBS declined to comment in its stance to an Amundi-style utility.

Credit Suisse may or may not be ready to sell its asset management activities, but lifting the unit out would showcase its structure and performance as an asset – as well as a potential deal counterparty.

Complementary Set-Up

So what would a Swiss tie-up look like? Its most striking aspect is that it far more sense than a full-blown merger, which would almost certainly run afoul of Swiss anti-trust officials, cost tens of thousands of jobs, and require a far larger capital buffer.

By contrast, in asset management, the two Swiss giants are even somewhat complementary: UBS hasn’t gotten very far into its private market efforts, where Credit Suisse has some expertise. Both are active in quantitative equity products, which could create scale.

More importantly, both are heading in the same direction: trying to create a broader asset manager with difficult-to-replicate products like private market offerings and liquid alternative products.