Credit Suisse’s top management wants to restructure its compensation system. A look into past policy reveals that risk was supposedly always taken into account.

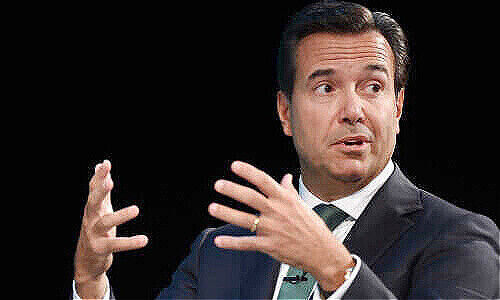

«We will design variable compensation in such a way that there is no longer an incentive to take excessive risks,» the Swiss bank's chairman, António Horta-Osório, said last Sunday. Linking compensation closer to risks is nothing new.

«Risk and control aspects are an integral part of the performance assessment and compensation processes,» according to the bank’s most recent compensation report. These measures are intended to ensure that the group's compensation approach is linked to risk and control processes and discourages excessive risk-taking, it adds.

Sound Familiar?

Similar wording appears in virtually all of Credit Suisse compensation reports from recent years. What is noticeable, however, is that in earlier years the financial figures on which the additional remuneration is based explicitly exclude goodwill amortization, real estate transactions, the sale of business units, restructuring costs and significant expenses for legal disputes.

The 2020 compensation report says that financial metrics would be established with respect to executive compensation that includes the full impact of material items and significant litigation accruals. So at least in doing so, «major accidents» and incentives for them would actually be excluded.

Holding Bankers Responsible

Comments the bank’s management has made about adjusting its compensation just don’t tie up with what it is saying today. Its management praises Credit Suisse's existing compensation system in connection with the Archegos losses of $5.5 billion, telling a Swiss outlet (behind paywall, in German) «those responsible were held accountable and $70 million in compensation were not paid out.»

Asked about the seeming contradictions between pay and lapses, Credit Suisse told finews.com it plans to detail revised compensation policies by mid-2022. The bank noted that it wants to more strongly link bankers' compensation with risk-taking and economic profits – in short, exactly that which past pay reports claim to have done.

Consistent Miss Of Goal

The issue comes against the backdrop of Credit Suisse’s checkered history of meeting its key profitability target. The return on tangible equity goal, shortened to ROTE, makes for one-third of the criteria for both short- and long-term bonuses.

Then-CEO Tidjane Thiam laid out a return on tangible equity target of more than ten percent in 2017. The Swiss bank never achieved this on an annual basis despite three grueling restructuring years under the former CEO.

Constant Adjustments

Instead, it went through several iterations and adaptations: by 2019, Credit Suisse had pledged to come in «around» ten percent the following year, down from 11 to 12 percent. By last year, when it did surpass ten percent two quarters running, the bank decided to adjust how it calculated the target, including factoring in a considerably lower tax rate.

The most recent interpretation of the target, set just last week by Chairman Horta-Osório and CEO Thomas Gottstein, is to hit more than ten percent by 2024 – a full seven years after the original goal was set.

Pressure On Profit

It stood at 1.5 thus far this year, following more than $5 billion in losses over Archegos’ collapse. By contrast, UBS recorded a ROTE of 15.5 percent thus far this year. Deutsche Bank, which targets more than nine percent but strips out a «bad bank», hit 7.3 percent in the third quarter.

Noting that Credit Suisse is again delaying improving its profitability, Fitch Ratings said Horta-Osório’s and Gottstein’s plans «entail execution risks given the need to strengthen risk culture after several risk control failures. Profitability will face near-term pressure,» in a note to investors.

Reporting by Rico Kutscher and Katharina Bart