Banking crises are difficult to prevent and why Swiss economic historian Tobias Straumann is skeptical of the «new» UBS. It could become too big for the Swiss financial center. Some precautions could help ensure a debacle like Credit Suisse doesn't happen again.

Less than a week before the announcement of the final integration of Credit Suisse into UBS, Swiss economic historian Tobias Straumann believes a major banking crisis in Switzerland is likely in ten or 15 years. «UBS is not safe,» he said Wednesday at a conference of the Fachschule für Bankwirtschaft (FSB) in Zurich.

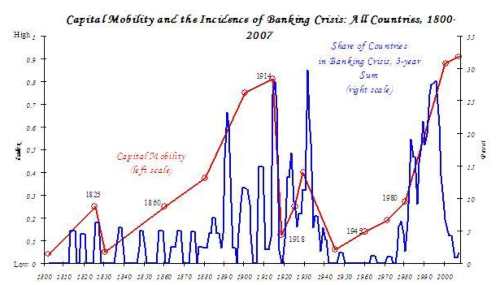

Straumann's bleak prediction isn't primarily related to the future organization of UBS, which will be fully unveiled next week, but mainly to historical logic and the fortunes or notorious inability of the supervisory authorities. In making his case he laid out the global relationship between capital mobility and the number of banking crises.

Capital Mobility is Crucial

With greater globalization comes greater capital mobility, resulting in more banking crises. This was evident between 1880 and 1914 when the degree of economic openness was very high as were the number of banking crises, as the chart below shows.

(Source: Carmen Reinhart, 2010; click chart to enlarge)

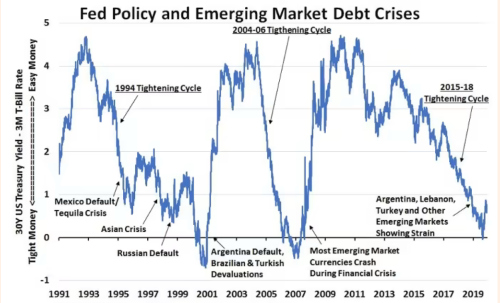

A similar pattern emerged in the 1980s and 1990s when globalization culminated in the dot-com bubble bursting. Unsurprisingly, more banking crises occur in times of rising or higher interest rates, which could be a cause for concern in the coming years as illustrated in the chart below.

(Source: Bloomberg/FT; click chart to enlarge)

The Adventure of Winding Down a Major Bank

The main determinant of whether there will be another Swiss banking crisis is whether the government and authorities implement a regulatory framework that would've avoided the situation that led to Credit Suisse's demise. Straumann said measures to reduce high-risk transactions by large banks have been demanded by the federal government for 25 years.

Such demands come to nothing for a simple reason. Economists Armin Jans, Christoph Lengwiler, and Marco Passardi wrote in their analysis «Crisis-proof Swiss Banks» that despite all the preparations, the liquidation of a major bank will remain an adventure, so the bank's management and Finma have strong incentives to delay resolution proceedings as long as possible.

Calling the Financial Fire Department

The authors sum up the dilemma over Credit Suisse. There's much to suggest that an earlier and more forceful intervention by Finma and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) might have prevented some things from happening. Better coordination between the SNB and Finma would certainly have been beneficial, Straumann explains.

He compares avoiding a banking crisis to fighting a fire. In addition to building regulations and building insurance, what is needed above all is a «financial fire department» that intervenes during a liquidity crisis or bank run. It can set limits for capital withdrawals, extend collateral for clients, or impose stricter regulations.

Another option is to introduce thresholds for credit default swaps that would force the authorities to intervene when breached, suggests Swiss finance professor Heinz Zimmermann.

Bold Consideration

Straumann's idea of increasing the equity ratio to such an extent that a bank like UBS would move its international business abroad for cost reasons is audacious since it would lead to losses initially. The «super UBS» now in the making represents an unfavorable and risky cost/benefit ratio for the Swiss financial industry. «Such a UBS would no longer be in the interests of the Swiss financial center,» Straumann observes.

Cooperation between Finma and the SNB is likely to determine whether and how another banking crisis will play out. Calls to build up more competence at Finma and increase the SNB's willingness to place its authority increasingly in the service of the supervisory authority might seem a stretch but shouldn't be dismissed out of hand.