Swiss lawyers are at the forefront of an effort to water down Switzerland's anti-money laundering law – and the alpine nation should brace for international pressure, author and financial crime specialist Balz Bruppacher tells finews.com.

Balz Bruppacher, how has Switzerland changed how it handles illicit money held offshore by dictators and strongmen?

The Marcos case in 1986 was a turning point: the Swiss government blocked money via emergency law for the first time when an associate of the toppled Philippine leader wanted to withdraw a three-digit million sum. It was heavily criticized by banks – the freeze happened hastily, on the sidelines of a state visit to Switzerland – but it set a precedent. Switzerland now has a defense mechanism in place against inflows of dictator loot. And banks emphasize that they are not reliant on this type of funds.

Switzerland is still associated with dictator loot and money laundering. Rightly or wrongly?

The era of African strongmen arriving on Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse with suitcases full of cash is definitely over. But as the world’s largest offshore haven, Switzerland still faces inflows of dubious origin. A decade after the end of banking secrecy, it’s become less about the mythology and more about tough competition. The case of BSI illustrates that even renowned houses aren’t always playing it straight.

The handling of dictator loot has shaped Switzerland’s reputation as a financial center. Is the country harming itself with its transparency?

In the short term, it may be a stumbling block. Further out, Switzerland won’t be able to afford walking the tightrope to adhere to international standards. Its stubborn embrace of banking secrecy for so long probably cost it more than benefited.

What about London, which is frequently criticized for equally discreet and often illegal practices around dictator money?

London and the U.K. have or had until Brexit a weightier international standing than Switzerland. It will be interesting to observe whether the U.K. can still afford to promote its financial center with a certain regulatory laissez-faire attitude.

Back to Switzerland: Bern and Swiss banks have at times enjoyed a cozy, then a more distanced relationship. What’s the right one?

I believe that too many close ties between banks and authorities are damaging. A strong financial center doesn’t need a state-run industrial policy. Authorities run the risk of regulatory capture. The government’s ordinance last year revising financial market supervisory law to allow closer control of Finma is a noteworthy example.

How useful is Switzerland for money of dubious origin, compared to other financial centers?

Probably not your first port of call, but the major money laundering cases just recently shows that Switzerland isn’t spared of white-collar crime.

What should Switzerland do to put daylight to these scandals?

Switzerland’s financial center will be abused by criminals as long as the country wants to compete among the top cross-border financial centers. What is important is consistently avoiding regulatory and judicial missteps. Recent developments from the criminal justice system don’t make me very optimistic.

Has Switzerland genuinely rethought its role around dictator money from strongmen like Suharto, Mubarek, and Gaddafi?

I don’t think the problem is primarily that of banks. Offshore company in tax havens as well as their advisers and helpers in Switzerland are a major blind spot. Lawyers are a powerful lobby in parliament, and they are currently working to dilute anti-money laundering laws to the extent that Switzerland should brace for another wave of international pressure.

Will digitization make it easier for criminal money to be transferred into Switzerland’s financial system?

I can’t make an accurate prediction. However, I view the euphoria of official Switzerland for the cryptocurrency and fintech sector with some skepticism.

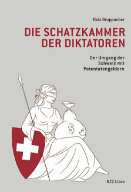

Balz Bruppacher is a decorated Swiss journalist and author of «Die Schatzkammer der Diktatoren,» a book on dictator money in Switzerland (in German only). The 69-year-old economist was responsible for the Associated Press’ domestic service from 1983 until 2010. He has written extensively about money laundering, including for «Neue Zuercher Zeitung,» and taught at Swiss journalism school MAZ.

Balz Bruppacher is a decorated Swiss journalist and author of «Die Schatzkammer der Diktatoren,» a book on dictator money in Switzerland (in German only). The 69-year-old economist was responsible for the Associated Press’ domestic service from 1983 until 2010. He has written extensively about money laundering, including for «Neue Zuercher Zeitung,» and taught at Swiss journalism school MAZ.