The Swiss bank’s Greensill troubles highlight decades-long ups and downs with investment banking. New Chairman António Horta-Osório’s most pressing task is a strategy review.

Credit Suisse CEO Thomas Gottstein had an eventful 12 months: faced with the outbreak of Covid-19 just weeks into his tenure last year, the bank scrambled to meet a government-backstopped loan bazooka.

The year went downhill from there after the Swiss wealth manager was forced to take a heavy hedge fund write-down, its private bank sputtered, «spygate» won’t die, and the whole bank is now mired in the scandal centered around asset management products with imperiled Greensill.

Shares Slid, Provisions Mushroom

Credit Suisse’s share price has slid as a result – by nearly six percent last week amid a downgrade by Goldman Sachs to neutral, from buy. The U.S. investment bank didn’t reference Greensill by name but justified its rating action with the specter of higher write-downs this year.

Credit Suisse’s legal provisions ballooned to 1.23 billion Swiss francs ($1.32 billion) last year; Goldman noted that it couldn’t rule out more legal pain for Credit Suisse to come. Regrettably, Gottstein can do little about this: most of the incidents pre-date his tenure as CEO, which began last February.

Avoiding Uncomfortable Questions

Most of the issues do, however, point to long-standing structural questions at Credit Suisse (as well as UBS, though to a lesser extent) over the sustainability of their universal banking models. The notion of offering clients various «touch-points» at the bank proved treacherous with Greensill, where Credit Suisse apparently did business in at least three different units.

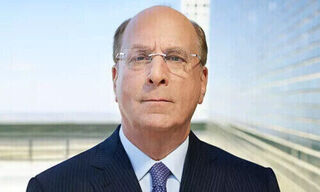

Credit Suisse’s ex-CEO Tidjane Thiam reversed the bank’s fortunes in a Herculean three-year effort, but Greensill lays bare that Chairman Urs Rohner avoided uncomfortable bigger strategic issues. It falls to António Horta-Osório (pictured below), who takes over as chairman of Credit Suisse next month, to unpick the wreckage and consider what it means for the Swiss wealth manager’s wider strategy.

Hitting The Ground Running

The subtle but continuous shift of trading bets into Credit Suisse’s asset management following the 2008/09 financial crisis raised the unit’s risk-taking, as finews.com highlighted last week. Horta-Osório, who will need to hit the ground running in Zurich after he leaves Lloyd’s at the end of next month, will have to tackle the bigger picture: how can Credit Suisse reconcile the riskier parts of its business with the steadier, recurring, and more boring wealth management revenues it seeks?

Culturally, Credit Suisse’s much-vaunted Swiss roots – historically entwined with the infrastructure development of Switzerland – have repeatedly clashed with its capital market ambitions.

Pantheon Of Wall Street

It was the first bank to break into Wall Street by taking over First Boston in 1990 and then Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette (DLJ) ten years later. The bold acquisitions led Credit Suisse into the pantheon – the top-five. At what price? Prominent critics including ex-Bank of England policymaker Paul Tucker question whether European banks like Credit Suisse have reaped a return on their Wall Street investments, viewed over several credit cycles.

Greensill is a thankless example: asset management, where the scandal lies, is not normally a high-risk business for universal banks. Credit Suisse has for years operated the unit as a series of boutiques with lighter-touch intervention from management, as finews.com reported – Greensill will put the kibosh on that.

19th-Century Founder's Vision?

As Credit Suisse comes into the crosshairs of disgruntled investors, Horta-Osório is likely to face calls to rethink investment banking and to more clearly ring-fence its asset management unit out of a private bank run by Philipp Wehle. This is hardly revolutionary: Credit Suisse’s rivals elsewhere have pooled their resources – something it and UBS have stopped short of.

A slimmed-down UBS would be in a position to plow money into growing its private bank through acquisitions – a takeover of Julius Baer, for example, is within the realm of possible deals – as well as pursue a much more focused strategy as a traditional merchant bank.

The latter would ironically return Credit Suisse to its roots as a financier, corporate lender, and adviser – precisely what Alfred Escher envisioned when he founded the Swiss bank in 1856.