In an interview, the former banker and current managing partner of the Orbit36 advisory emphasizes that rules aimed at recapitalizing and stabilizing financial institutions are not what Credit Suisse needs right now.

Mr Ita, your Orbit36 risk consultancy has been thoroughly analyzing the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). The shockwaves from California have led to a steep drop in Credit Suisse shares and a lifeline from the Swiss National Bank (SNB). Are we facing a new banking crisis?

In my opinion, SVB is a glaring, but isolated incident. A sizeable bank that simply didn't have its interest rate risks under control. Regulation in Switzerland or the EU would have prevented that from happening in that fashion. Still, market participants and other institutions, are still facing two questions. What banks still have unknown risks on their books and where are the potential counterparty risks?

Does that mean we are facing a crisis of confidence?

That would clearly explain the substantial decline in bank shares worldwide and the current turbulence that Credit Suisse faces. Loss of trust can fundamentally bring any bank to its knees.

«Large investment banks have to refinance their trading books daily»

According to the media reports, the fact that the European Central Bank (ECB) asked eurozone institutes to disclose their positions vis a vis Credit Suisse sent problematic signals to the interbank market. A general loss of confidence in a market critical to short-term financing needs in the banking sector could become extremely dangerous for other institutes and lead to liquidity shortfalls. The banks that are most suspicious in that case are those that are generally perceived as being weaker or harder hit.

The last time we had such a crisis of confidence was at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. At the time central banks had to make massive interventions in the market. Are we about to experience another liquidity crisis?

Whatever the case, there is something in the air. One has to understand that large investment banks have to refinance their trading books daily. If other banks refuse to lend to them, that can impact the affected institution almost overnight. In the very short term, they could find that they have a funding gap that runs into the double-digit billions.

Is that what happened to Credit Suisse on Wednesday?

It is possible given the numerous negative media reports and if, in fact, the ECB did actually exacerbate any uncertainty in the interbank market.

André Helfenstein, the head of Credit Suisse's Swiss business, said on Wednesday that the direction of a bank share price currently seems to mirror its perceived safety on a 1:1 basis. If that is true, will the bank see further client outflows?

In my experience working in the treasury of a bank, I can say that savings deposits and private banking asset outflows do not necessarily precede or follow each other immediately. What is harder to judge is when a bank can no longer access any funding on the interbank market. The share price can indeed be seen as a sign of confidence when it comes to that.

«Evey central bank has liquidity facilities ready»

But that can become an unjustified self-perpetuating eventuality. If I think like a shareholder and believe that others could lose their faith in the bank, whether justified or not, it is rational to sell my shares in the expectation that this might lead to bankruptcy. Because if it comes to bankruptcy, shareholders normally don't get anything, in contrast to a bank's clients. But this kind of spiral can also lead to exaggerated reactions and unnecessary uncertainty, such as what we experienced the day before yesterday.

The SNB put 50 billion francs (circa $54 billion) in short-term liquidity at the disposal of Credit Suisse. Is that enough to stabilize it?

One has to assume that the sum involved met the needs of the bank at such a moment. Every central bank has liquidity facilities ready that help banks get through possible shortfalls. It is a conventional instrument and it should not be confused with government intervention or assistance. Such facilities are conditional on a bank still being solvent. The institution in question has to provide high-quality assets, such as securities, as collateral. That means that taxpayers will not be shouldering any losses from that kind of business.

Still, Credit Suisse is being propped up with billions. Is that not continuing to adopt a too-big-to-fail posture in an almost absurd fashion? The relevant rules should allow for system-relevant banks to go under when they have put themselves in situations like this.

I don't think that too big to fail is the right answer for Credit Suisse's current difficulties. The bank has enough capital. It has a common equity tier 1 ratio of more than 14 percent. It is more than adequately capitalized and it has not, as far as we know, suffered any large losses.

«Credit Suisse probably needs the billions as a preventative measure»

The too big to fail instruments are there for exactly that. To compensate for a bank's losses and provide them with enough of a capital buffer. In extreme cases, they are there to dissolve a bank without having to resort to taxpayers. Both Credit Suisse and UBS hold almost $110 billion in capital to cover losses in crises. That does not contribute anything to their liquidity as it is there for another purpose.

Why does Credit Suisse need the money?

Credit Suisse probably needs the billions as a preventative measure to be able to stem larger outflows and to avoid them in advance.

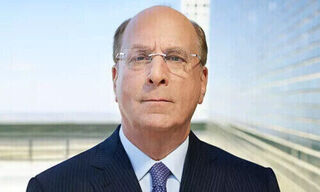

Andreas Ita is the founder and managing partner of Orbit36, a company that advises banks and insurance companies on strategic planning, risk, and capital management. The Swiss banker started his career in equity derivatives trading and worked for UBS for a total of 22 years. Most recently, he headed the Group Economic Performance and Capital Optimization team at the Swiss bank until mid-2019. He holds a Ph.D. in Banking and Finance from the University of Zurich.