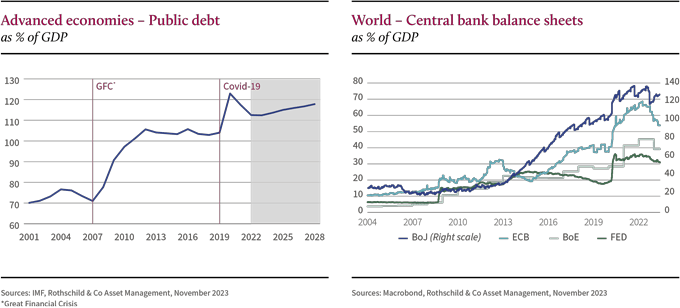

Advanced economies’ debt burden hit historic levels in 2020, and debt/GDP ratios have spiked, due to the combined shocks of the great financial crisis and the pandemic. Are we headed for a sovereign debt crisis?

By Marc-Antoine Collard, Chief Economist & Head of Research, Rothschild & Co. Asset Management

The notion of sustainability of public debt is rather subjective. Nevertheless, in the broadest sense of the term, a debt is deemed sustainable when the borrowing state is able to honour its present and future obligations while conducting economically feasible and politically realistic policies.

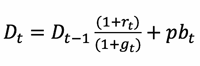

In a theoretical framework, debt dynamics can be expressed as follows:

where Dt is the ratio of public debt as a percentage of GDP.

The debt trajectory therefore depends mainly on three variables. First, on the real interest rate «r», which is positively corelated to debt, as high rates exacerbate the debt burden. Second, debt is negatively correlated to real growth «g», as robust economic activity generally produces higher revenues for the state, thus improving public accounts. Third, debt dynamics are positively correlated to the primary deficit (pbt), as spending above receipts increases the debt burden.

Navigating Debt Sustainability: Challenges Amidst Economic Shifts

Hence, the lower interest rates are compared to economic growth (r<g) , and the lower the primary deficit, the more sustainable a debt will be.

And, until recently, the accumulation of public debt posed little risk in light of the economic context. With inflation staying very low during the post-financial crisis years, central banks applied an accommodative monetary policy by massively buying sovereign bonds under their quantitative easing programmes and by keeping their key rates low and even negative in some cases. As a result, low interest rates made financing of deficits much easier.

Pandemic, Inflation, and Sustainable Debt

But the pandemic profoundly altered the macroeconomic landscape, and that has put the spotlight back on the sustainability of public debt.

For, central banks are once again having to deal with inflation, which has hit 40-year highs. The resulting tightening cycle has pushed up sovereign yields, thus making it more expensive to service sovereign debt. Moreover, given the stubborn pressures on core inflation, central banks may have to keep rates higher for longer, thus maintaining upward pressure on the «r» variable.

(click graphic for large view)

Inflation’s Ambiguous Impact on Public Finances

The debt/GDP ratio has receded since inflation returned in 2021, and some investors see it as a miracle solution to the debt problem.

In the short term, inflation generally lowers the debt ratio, as when prices rise, nominal GDP (the denominator) surges, which automatically lowers the debt/GDP ratio. Moreover, state income rises in parallel with prices, particularly through higher VAT receipts. This narrows the deficit.

In the longer term, however, indexation of some public goods and services (wages, pensions, etc.) raises governments’ primary expenditure, which, in turn, exacerbates the deficit. The same effects are caused by support measures that are generally taken to offset inflation’s impact on household and business purchasing power.

There is also the matter of the debt structure. If debt consists of maturing short-dated bonds, those bonds will have to be rolled over at higher current interest rates, thus increasing the debt burden. Likewise, if the debt includes inflation-linked bonds, debt-servicing costs will surge.

In short, inflation does lower the debt ratio in the short term, but this doesn’t last and is not a permanent solution to the debt problem.

Marc-Antoine Collard started his career in 2004 as an economist for the Canadian Ministry of Finance and then as a strategist-economist for the Caisse de dépôts et placement du Québec for 5 years. In 2011, he joined Société Générale as Country Risk Economist for the Americas and Gulf countries, and Head of Commodities Research, notably energy. He joined Rothschild & Co Asset Management Europe in 2014 as Head of Macroeconomic Research. He is also a lecturer in macroeconomics at Sciences Po Paris. He holds a master's degree in economics from the University of Quebec in Montreal and is a CFA charterholder.