With the end of the emergency law, the federal government and UBS want to return to business as usual after the Credit Suisse takeover. It's precisely what's causing friction as the deal comes under fire.

«As of today, the Confederation and the taxpayers no longer bear any risk with regard to the state guarantee,» Finance Minister Karin Keller-Suter, commented on UBS's decision last Friday. The bank concluded that the loss guarantees for Credit Suisse securities, which was taken over in March, were no longer necessary.

She explained there's no longer a need for emergency law, intending to signal to the public and the markets in the country that a controversial issue is no longer on the table.

More Activity Expected

That's likely to prove wishful thinking. On Sunday, an announcement from the Swiss Investor Protection Association (SASV) made the rounds. The organization intends to sue for the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS in the Zurich Commercial Court today. The association says it represents more than 500 investors who lost money on the bank's mandatory convertible bonds (AT1) written down as part of the Credit Suisse bailout.

They join some 1,000 injured parties who feel the nearly $16 billion write-down ordered by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (Finma) was unlawful and are pressing for compensation. Legal representatives for the investors announced further steps in the coming days.

Irritation Abroad

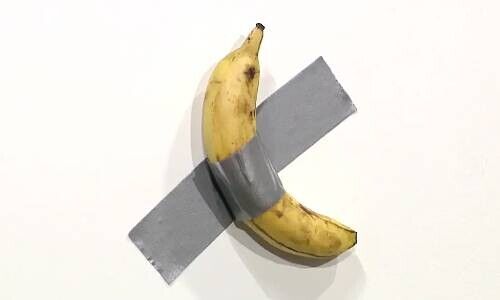

This is causing irritation abroad. «Bloomberg» (behind paywall) recently observed that people in Switzerland have quietly gone back to earning money. A «Financial Times» (behind paywall) commentary was even more explicit, saying it remains to be seen whether the country is a banana republic or a poster child for honesty, following the situation with Credit Suisse.

Is Switzerland a banana republic? The typical reflex in this country to such accusations is to dismiss them as deliberate American-British polemics. After all, the Swiss financial center is in tough competition with Wall Street and the City of London.

But sometimes even a successful player like Switzerland which remains the world's largest offshore financial center, is well advised to polish its external optics.

Just Leave it Alone

It's astonishing how quickly the outrage over the latest bailout of a major Swiss bank has died down. To be sure, parliament hasn't yet given its blessing to the deal. But the fact that competition law was circumvented to save Credit Suisse and UBS was granted a moratorium on equity until 2029 is hardly causing rumblings in the Federal Council.

Last fall, then-finance minister Ueli Mauerer declared Credit Suisse should be left alone. This statement, in retrospect flawed, seems to have been extended to UBS. The federal government and the supervisory authority have given the Credit Suisse buyer significant leeway to make the forced takeover a success.

This and the conspicuous silence suits UBS management very well, which is still discussing the complete integration of Credit Suisse. There should be news on this at the UBS second-quarter results conference on August 31. The writing is on the wall, with around 35,000 jobs under threat of elimination. In Switzerland, 12,000 jobs are expected to be shed if Credit Suisse's Swiss operations are merged into UBS.

Smoking Gun

As the SAV's actions show, the merger could be caught in the crossfire before the deadline. Foreign commentators and more than 1,000 plaintiffs worldwide challenging the write-off as unlawful, see a smoking gun.

According to the too-big-to-fail regulation, two preconditions needed to be met to trigger mandatory converters. An undercapitalization of Credit Suisse, and a government cash injection. As both Keller-Sutter and Finma leaders acknowledged since the March bailout, Credit Suisse wasn't undercapitalized but had a liquidity problem. To that extent, only the preconditions of the state aid had been met.

According to media reports, as late as mid-March Credit Suisse's legal department believed the mandatory converters could not be triggered under the prevailing circumstances.

Forced Court Disclosure

The emergency law that went into effect on March 19 changed that. Finma was allowed to trigger the mandatory convertible bonds even in the event of liquidity problems, which it did. From the point of view of investors as well as foreign commentators, it looks as if the Federal Council abruptly changed the rules of the game. That Finma had to be ordered by the Federal Administrative Court in May to decide on the write-off available to the plaintiffs doesn't cast a good light on the actions of the federal government and the supervisory authority.

The Federal Administrative Court is being silent for now. It's not even possible to find out when the deadline for filing lawsuits ends. Judges in St. Gallen may be waiting for the results of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (PUK) into the takeover before rendering a decision, and likely to fuel suspicions of a Swiss cover-up.

No Business is Risk-Free

Keller-Suter said Friday that conditions surrounding the AT1 securities were regulated in the contracts as part of the risk and return profile. While feeling sorry for investors who lost money, she said «as a liberal politician: there is no business without risks.»

This last statement likely won't sit well with AT1 investors. In any case, voices criticizing the cancellation of the state guarantee for UBS show the situation of Credit Suisse was never so dire that Finma needed to write off the mandatory converters. As far as these claims are concerned, Switzerland is probably still a long way from closing out the Credit Suisse debacle.