Investment banking should be kept separate from the rest of the industry and there are time bombs buried in the markets waiting to explode. With much foresight and thanks to decades of experience, Walter Wittmann, who died earlier this month at the age of 80, put pen to paper on issues haunting the financial markets to this day. This essay was first published on November 6, 2013, by finews.ch.

This feature by Walter Wittmann is the 10th contribution to our section finews.first. It is a forum for renowned authors specialized on economic and financial topics. The texts will be published both in German and English. The contributions appear in cooperation with Pictet, the Geneva-based private bank. The publishers of finews.ch are responsible for the selection. Previous contributions: Rudi Bogni, Adriano B. Lucatelli, Peter Kurer, Oliver Berger, Rolf Banz, Dieter Ruloff, Samuel Gerber, Werner Vogt and Claude Baumann.

The topic has been hotly disputed for years: should big banks with investment divisions be broken up? There are plenty of reasons for such a move. Investment bankers sent the world tumbling, through crashes of the market, financial crises and depressions – for instance in the 1930s.

The time from 1830 through the American Civil War in 1861–1865 was the era when the investment banks were founded. A string of institutes came into being. The turn was on a whole new generation of speculators with a hitherto unknown degree of unscrupulousness (aptly described in «Wall Street: A History», by Charles R. Geisst).

The completely unregulated environment fostered speculation. Equities, bonds issued by cities, states and the federal government in Washington D.C. gained in importance. Short sales on a large scale triggered one crisis after another.

There were no consequences drawn. Charles R. Geisst, a professor of finance in New York, distinguishes between those years as an era of fraudsters and the years of 1870 to 1890 as the era of robber barons.

«Speculation became excessive in the Golden Twenties, fueled by loans»

Domestic and foreign investors were put off by the crash of 1873, but only for a short while. Soon, they returned to the markets. In the years from 1880 to 1910, the world of business was confronted with a fundamental innovation: it was the beginning of the era of trusts. They bought small- and medium-sized companies, bypassing the investment banks such as Goldman Sachs. The method of payment used were certificates issued by the trusts traded on the stock exchange, and not money.

In the absence of a financial market regulator, there was no way to stop manipulations. And the powerful families, such as the Carnegies, Rockefellers and Vanderbilts, were going along with this.

Fueled by loans, speculation became rampant in the Golden Twenties. Investment trusts were used as vehicles. Money was borrowed to buy selected stocks deemed suitable for manipulation. The price of the trusts were pushed to dizzy heights – before the bubble burst. Numerous investment trusts had gone bust even before the great stock market crash of October 1929.

Based on the bad experiences with the crash of 1929 and the subsequent global depression, a fundamental rethinking was taking place. In 1933, the U.S. passed the famous Glass-Steagall-Act, separating investment banking from commercial banking. Henceforth, investment bankers were barred from receiving client assets and undertaking underwriting business at the same time.

«Derivatives were issued with attractive names to give the impression of secure investments»

In the 1980s, investment banking received a fresh impetus, thanks to several innovations. On the one hand, loans became securitized – mortgages, grants, student loans and even credit card loans(!). In reality, this merely led to an increase of existing products, a transformation into artificially constructed and tradable securities.

The securitization also created a second money flow independent of the central bank. Derivatives were issued with attractive names to give the impression of conservative and secure investments.

In the second half of the 1990s, markets were liberalized:

- The U.S. mortgage market was fully liberalized in 1995.

- Immediately before the tech bubble burst in the year 2000, the Glass-Steagall-Act of 1933 was lifted. And with it the separation of investment and commercial banking.

- In 1999, speculative investments such as futures were liberalized.

«The problems, which prompted the financial crisis, haven't been solved to this date»

This paved the way for a breath-taking development, leading to the financial and economic crisis starting in 2007.

The problems, which prompted the financial crisis, haven't been solved to this date. The debt crisis has actually deepened. This is a time bomb waiting to explode, in particular concerning the convertible debt swaps. The biggest problem however are the derivatives markets, which boomed since the 1990s. We are talking about $700,000 billion. With a wafer-thin capitalization as security.

Here – and elsewhere – we are waiting for disaster to strike. We are facing the collapse of the global financial system.

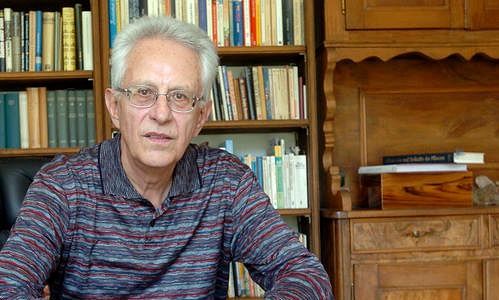

Walter Wittmann was a Swiss economist. He shaped the department of economics at the University of Freiburg during his three decades as professor at the institution. Born in the canton of Grisons, he was the author of numerous books that offered insights into the workings of the financial markets. In 2007, he published «Der nächste Crash kommt bestimmt», and in 2010 he predicted the bankruptcies of states in «Staatsbankrott». Wittmann died on February 12th, 2016 at the age of 80.