UBS is occupied with a mega-merger of its U.S. brokerage and its wider, international private bank. What does the Swiss bank stand to gain from the project?

The move represents a mega-merger of two of the world's largest wealth managers: UBS is stitching up its U.S. brokerage, which manages more than $1 billion in money on behalf of North and South American clients, with UBS wealth management, which pitches in another roughly 1 billion Swiss francs ($1.04 billion), mainly in Switzerland, Europe, and Asia.

While the two units have moved closer together in recent years, their full merger carries considerable risks: the brokerage model and the advice-focused approach common in the rest of the world are very different.

Risky Dual-Head Structure

The novelties begin at management level, where UBS has been the so-called global wealth management unit in the hands of two executives: Martin Blessing, who ran Commerzbank until two years ago, and Tom Naratil, a 35-year veteran of UBS. The private bank's former head, Juerg Zeltner was diametrically opposed to a unit merger – which may have been the reason that he left the Swiss bank abruptly in December after 31 years.

So why merge? UBS' public reasoning so far has been that it helps the bank's chances with the type of super-rich clientele it is increasingly pursuing, including in Asia and Latin America. The proposition is striking: by drawing its units together, the world's largest private bank can enable deal-making across several continents (forgetting the minor detail of regulatory barriers for a moment).

Where are the Synergies?

Another angle of UBS' reasoning is that its newfound heft will allow it to negotiate lower prices from fund managers and other financial providers. The merger also highlights its IPS unit, or investment platform and solutions, which should be able to place more complex financial products, in more of the world.

These reasons are sensible – but beg the question of cost synergies from the merger. Consulting firm Trefis took on the conundrum and came to the following conclusions:

1. Forecasts, Without Mega-Merger

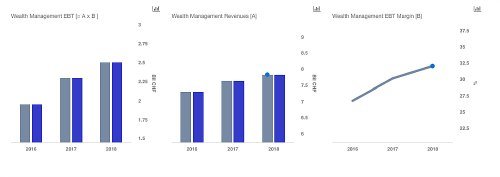

Trefis predicts revenue growth of 2.5 percent for UBS' «old» private banking unit to 7.8 billion francs, and a 2-basis point margin fillip to 32 percent. This translates to a 2.5 billion franc pretax profit – without the merger.

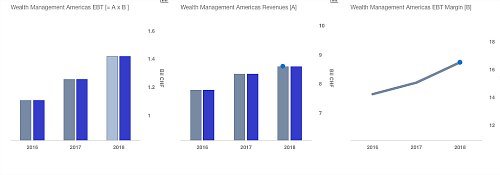

The U.S. counterpart posts better revenue growth – 3 percent to 8.6 billion francs. Trefis expects a margin climb to 16.5 percent, from 15 percent currently. This means a year-end pretax profit of 1.42 billion francs, again before merging.

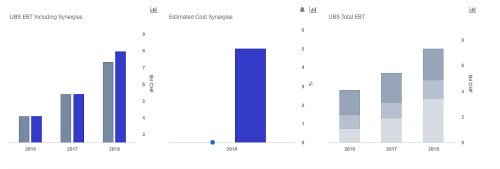

The analysts expect a pretax profit overall for UBS of 7.3 billion francs – without the private bank mega-merger.

2. Lower Post-Merger Spending

Trefis predicts a 5 percent spending cut by merging, mostly because UBS will be able to cut back- and middle-office jobs through the move. The bank will also be able to flex its muscle on pricing, as well as negotiate better conditions. These measures will bolster UBS' pretax profit by 8.6 percent – or to 7.95 billion francs, from 7.32 billion previously.

Clearly, Trefis sees the mega-merger as not just beneficial for clients, but also for shareholders: if UBS lifts its pretax profits by the 9 percent predicted, the stock will respond. A share price prediction would be presumptuous, but UBS boss Sergio Ermotti may finally get his wish for some love and acknowledgement from investors for his five-year efforts to revamp UBS.