At UBS, the focus on wealth management was born out of necessity during the financial crisis. One global crisis later, that strategy is helping it leave global competitors behind.

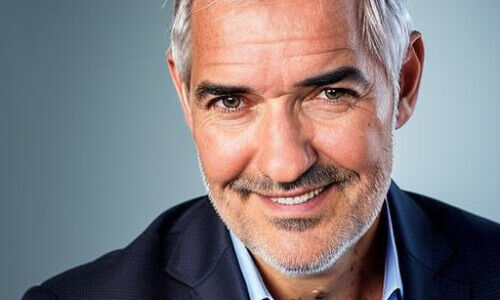

Lower profits, less money invested by clients money, and fewer bonuses for advisors. At first blush, the third quarter has not been very promising for UBS's core wealth management business. But according to reports from within the bank, the team around Iqbal Khan (pictured below), the sole head of the Global Wealth Management (GWM) division since the beginning of October, is patting itself on the back.

It delivered a pre-tax profit of $1.453 billion, a scant 4 percent below the previous year's quarter, and 14 percent better than the analyst consensus. The division contributed the lion's share of the group's pre-tax profit of $2.323 billion.

(Image: UBS)

Geared for Wealth

By contrast, Wall Street banks suffered from an investment banking slump in the third quarter, hamstrung by higher interest rates, the war in Ukraine, and soaring energy prices. Only now are JP Morgan, Citigroup, and Goldman Sachs turning their attention to asset management and the steady returns that this business promises.

In wealth management, UBS has emerged from adversity to become the world's largest provider of such services. After horrendous investment banking losses from bets on toxic credit securities and a government bailout in 2008, then Chairman Axel Weber and former CEO Sergio Ermotti (pictured below, from left) undertook the task of trimming the institution entirely to private banking for the world's rich starting in 2011.

The next leadership generation is managing this strategic legacy quite skillfully. In the past nine quarters, UBS's pretax profit has never fallen below $2 billion.

(Image: UBS)

Toeing The Line

The GWM division's relationship managers demonstrated they could keep their wealthy clientele in line, an important consideration in times of turmoil to stay the course. While clients were de-leveraging and liquidating loans on assets, as in Asia, the bank was able to attract deposits and new money which generated fees. Absent that, like in Switzerland, UBS was able to increase cash deposits and loans, an indication clients did not leave the bank, but rather took advantage of other services.

To be sure, not all is peaches and cream and there are still some downsides. The GWM division is not generating enough profit, with the bank's management setting the pre-tax profit target growth between 10 to 15 percent. The result so far this year is a 7 percent decline. Likewise, the decline in fee-generating assets is not good news. After all, a private bank that functions as a mere vault for the cash of the super-rich is of little interest from the point of view of investors. Moreover, the ambition of increasingly serving smaller- to mid-sized assets was dealt a blow with the exit from the Wealthfront deal in the US.

Disharmony Risk

That is a cautionary development that UBS management should not bask in its achievements, a danger that is lurking. The success of the GWM division is fueling speculation that division head Khan is already set as the next UBS boss. A recent detailed «Bloomberg» (paywall) story suggested palace intrigues at Switzerland's largest bank, with Group CEO Ralph Hamers seen as a victim, although it is not least thanks to his refraining from major interventions on the operational side of the business that it is running at full speed.

At the same time, the bank can by no means afford to slow down in its digitization efforts, the pet project of Hamers. UBS's rise to become the world's largest private bank is due in large part to the effective cooperation of the «Webermotti» team. The new leadership in the form of Chairman Colm Kelleher, CEO Hamers, and GWM division head Khan might be well advised to emulate their predecessors in this respect.